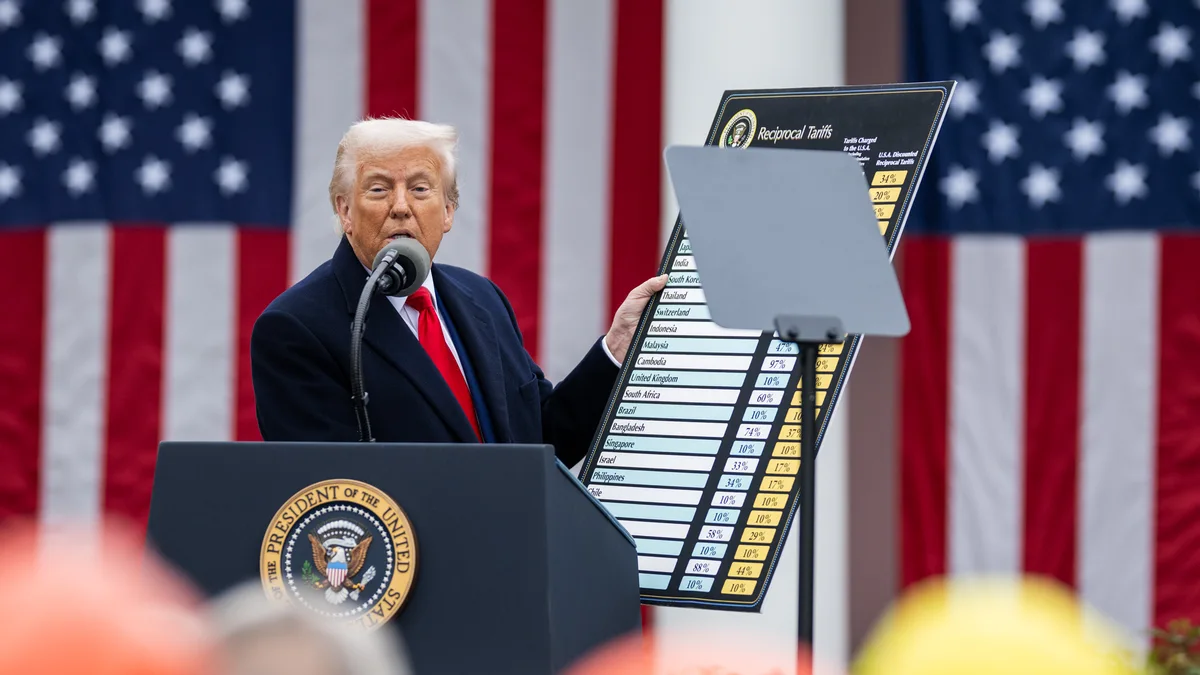

Trump’s tariffs are set to take effect today, and if the stock markets are any indication, it would seem that the first major shots of this trade war have been fired. That being said, while the Philippines is one of the countries featured in the grade-school-level illustration board presented by the US president, our exports are only being charged 17%, which is relatively tame compared to our neighboring ASEAN countries.

Vietnam will get a 46% tariff, Thailand is at 36%, and Indonesia lands at 32%. This is in stark contrast to the current tit-for-tat between China and the US, with the latter threatening the former with a 104% tariff, meaning trade between the two largest economies in the world is basically dead, or about to die.

While these tariffs are not applicable to foreign imported cars, which are hit with a standalone 25% tariff for cars produced outside the US, knowing the fickle nature of the current administration it is not out of the question that this might be later applied to existing tariffs.

But what does this mean for us? We don’t really export to the US, so we should be safe, right? We can even export to the US with lower costs than our neighbors, won’t this allow the Philippines to export more to the US? Not necessarily. Hate to say it, but we may end up in the line of fire in this economic war.

What are tariffs?

Put simply, a tariff is a form of a tax; it is imposed by a government on goods imported from other countries. It can raise revenue, and is more often used to give preference to locally produced goods as a form of protectionism. Worse, they can also be used as retaliation, a punitive measure against other countries.

What are the Trump tariffs?

On April 2, 2025, President Donald Trump announced “Liberation Day,” wherein he imposed tariffs on almost all the trading partners of the United States. This resulted in a 17% tariff on the Philippines, among others we have already mentioned.

While he calls these tariffs “reciprocal,” this has largely been disputed, as the equation used by the Trump administration involves the trade deficit, or how much the US imports vs. how much they export to a certain country. This means that Trump’s tariffs are not based on how much tariffs the subject countries are actually imposing on the US, but how much the US buys (imports) than it sells (exports) to said country, which, most economists agree, isn’t a good metric, as a trade deficit in itself is not a bad thing. The US is a consumer economy after all. All in all, more than 100 countries are covered by the new tariff regime.

Who pays for the tariffs?

This is where most of the issue lies. Despite popular misconception, these tariffs will be paid for not by the countries exporting goods to the US, but by the companies and consumers themselves. This is because tariffs are charged as part of import duties upon arrival of the goods. Hence, if the value of a good is $100 upon landing, but they are charged a 10% tariff, there will be another $10 charged on top of that, which will be charged to the company bringing in that foreign good into the country.

That also means, however, that the companies bringing goods into the US are free to pass this cost onto the consumer (assuming that they are taking the risk of lower sales with higher prices), which means, at the end of the day, prices will most definitely increase, as the cost of importing the goods may be taken into account.

How may this affect the Filipino automotive industry?

The Philippines does not export so much to the US, which means we should be safe right? But this is not normally the case. You see, with tariffs extremely high on certain countries, like Japan for example, where they are set to be hit with a 24% tariff on its exports, which is separate from the 25% tariff on automobiles made in Japan (which was already in place prior to “Liberation Day”), companies that export to the US, such as Toyota, Mazda, and Honda, may want to keep exporting to one of the largest car markets in the world.

This leads to a few possibilities: 1) The car brands shoulder some of the costs of the tariffs to remain competitive. 2) They can increase prices to pass on the cost of doing business in the US to other markets that they export to, like the Philippines.

The latter is worrying, as this means that car brands that are affected by the tariffs, which is almost all of them, especially those from China, may increase their local prices to subsidize the increased cost of selling to the US. This would result in a price hike across the board. Which of these will happen? Only time can tell, to be honest, as everything seems to be in flux at the moment while catering to Trump’s whims.

The last possible consequence is losing some brands completely. Especially with China imposing retaliatory tariffs on the US, it would seem that both countries’ economies will definitely suffer. Can all the new Chinese car brands survive such a blow to their economy? Can some of the Japanese or European brands survive the reduced exports to the US? We really don’t know at this point, but it wouldn’t shock us to see some brands disappear or consolidate as everyone is just trying to survive this trade war.

Won’t brands open manufacturing here with our lower tariffs vis-à-vis our neighbors?

That certainly is a possibility. After all, compared to other ASEAN countries, we do have one of the “lowest” tariffs in the region. However, it is extremely unlikely.

It takes many, many years to invest in a country and put up a manufacturing facility, and Trump is only in office until January 2029. That is just four years. That’s four years of instability, but with Trump’s team offering “renegotiated” rates to countries, and knowing how wishy-washy this administration is, car parts suppliers will hesitate to invest multiple years and billions of dollars to counteract tariffs that can be gone in four years—or gone tomorrow.

It just does not make sense. It makes more sense to wait and see, which is the most prudent option given how everything is in a state of flux at the moment. We doubt any company would do a 180 and relocate manufacturing at a moment’s notice.

What can we as a country do about these tariffs?

Not much, to be honest. Our economy is small enough that we are nothing more than collateral damage in this trade war. We can only hope that cooler heads prevail, and stability is returned to the world economy soon. We have come too far with open global trade to go back to protectionism and isolationism based on one illustration board held up by the leader of a nation.