You could be forgiven for missing the significance of this car. It looks like an ordinary—if elegant—Japanese big sedan. Inside and out. It rides and steers like one, too, though extremely refined and well-sorted. The ordinariness is of course precisely the point.

The Mirai is the fuel-cell car going mainstream. It drives like a big EV, goes further on a tankful than they do on a recharge, fills up in 10 minutes, and costs less to buy than a big 480km battery car.

Is that the smell of exotic dung? Open the window, while we address the elephant in the room. Even here in Britain, where we are reviewing the Mirai, there are only a dozen or so public hydrogen stations. So, you won’t be getting a Mirai unless, say, you run a regional taxi or limousine company and are near a hydrogen pump. Or indeed can install your own.

There are good arguments why hydrogen can in future exist alongside and complimentary to pure-battery cars. Especially, too, why it’s a great solution for local bus and truck fleets that do regular runs. Once those commercial fleets are established, there will be more hydrogen available for cars, and that means more cars will be sold.

But we’re here to talk about the Mirai itself. The outgoing Mirai looked like the science project it was. The new one is a car. And an uncontroversially pretty one, its big wheels emphasizing the low, shark-like fascia and the fastback tail.

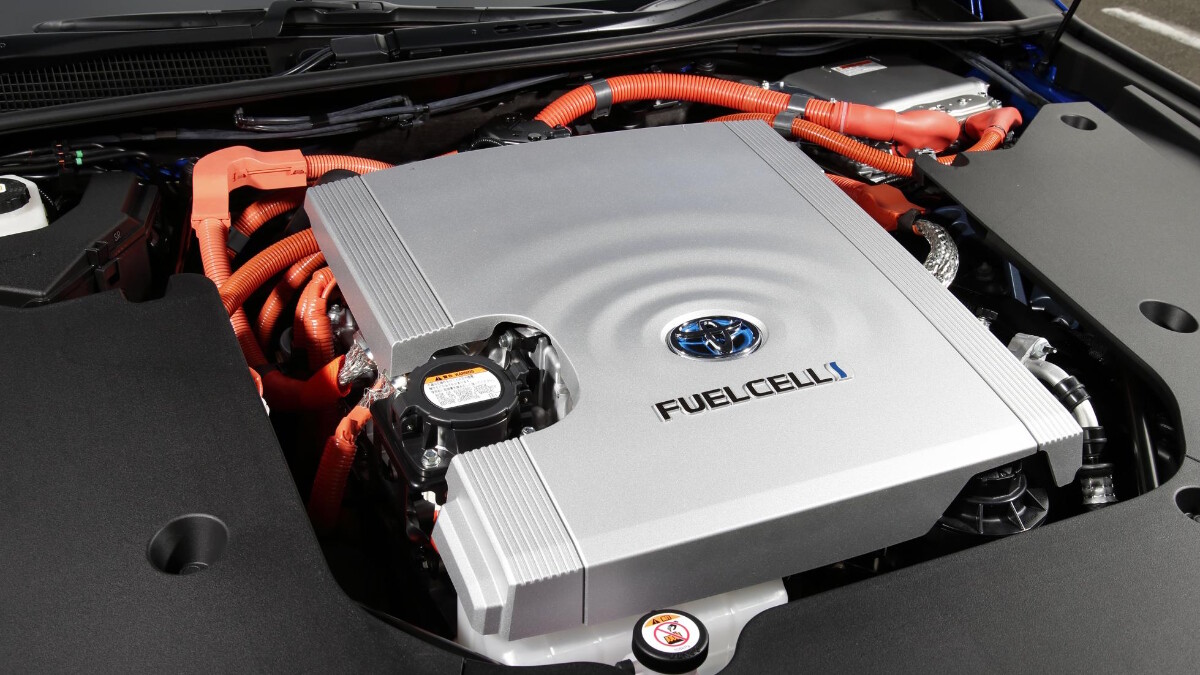

You know the fuel-cell drill. High-pressure hydrogen is kept in cylindrical tanks in the car. The new Mirai packs one tank along the center tunnel, one transversally under the back seat, and another under the trunk. The hydrogen is admitted into a ‘stack’ of fuel cells. Purified oxygen is pumped into the other side of each cell, separated from the hydrogen by a membrane.

The hydrogen atoms WLTM oxygen, and to do it, they shed their electrons so their nucleus, a proton, can permeate through the membrane. The liberated electrons jump around the cell, via circuits that power the car’s drive motor. The hydrogen, oxygen, and returning electrons combine to make pure water, the only emission.

The new-gen Mirai’s fuel-cell stack has been reduced in cost, as well as in physical size. So, it can live under the hood, along with the oxygen fans and purifiers and high-voltage electronics. The drive motor is at the back, whereas the old Mirai was FWD. Above the motor is the hybrid battery.

Yup, it’s a hybrid, because that means the fuel cell’s output needs only be sufficient for continuous cruising, while the battery can augment that power to give the motor an extra kick during all-out acceleration. Also, it gives better response, because any fuel cell is a bit laggy. But don’t worry: The Mirai sidesteps the Prius rubber-band effect because the motor drives the wheels directly through a single fixed gear ratio.

The 3D jigsaw of all these systems is fitted in a way that matches for space the components in a rear-drive gasoline hybrid. So, the Mirai has a rear-drive platform shared with new Lexus cars. That’s good for comfort and quietness, and proper multilink suspension all around gives hope for an improvement on the original Mirai’s canoe-like dynamics.

For its manufacturer, this new Mirai is a proper business, not a low-volume proof-of-concept. Toyota expects to sell 30,000 a year, which is about the same as BMW sells of the i3. Even a company as big as Toyota can’t afford to sell that many cars at a huge loss. This shows that fuel-cell cars are now getting close to cost parity with those big-battery pure-electric cars the Mirai competes against.

While it’s a better and better-equipped car than the old one, it’s going to be 20% cheaper to buy or lease. That would put it—exact numbers aren’t out yet—at roughly £53,000 (P3.41 million).

On the road

Relax. It might be driven by an electric motor, but it’s not about a 500hp stampede. Instead, it’s gentle, smooth, and comfy like Sunday afternoon.

The 182hp motor gives a sprightly step-off, and smooth seamless acceleration. But a 0-100kph time of 9.2sec better suits gentle chauffeuring than chasing assertive German sedan drivers down the autobahn. The Mirai’s urge will tail off above 100kph. That’s not to say it’s incapable of swimming in the outside lane, but you need to plan your moves. Steering is mute but accurate, and it tracks nicely about the straightahead.

Lob it at a bend, and there’s a moment of slack while it asks you if your backseat paying passenger really wants this. But then, after due consideration...around it goes, flat and pretty sure of itself. Give it the beans (admittedly, only one of those little squat bean tins that are no use to anyone) and you feel the rear tires shoulder the effort and shove you through.

It’s not too much of a barge, then. It’s less than two tons—not bad for any five-meter-long car and a whole lot less than a battery-powered equivalent.

The cornering is certainly more level than you’d expect from its lovely, supple ride. It absorbs biggish undulations and sharp hits and smaller untidiness with equanimity. There’s not a lot of road noise, either. Nor the cacophony of whirring fans and pumps that were always present in the old Mirai.

Our test trip didn’t include a lot of highway driving, but the driver assist worked to normal posh-car standards.

On the inside

This is a Toyota. But by the swish materials, the plush furniture, and the sense of lux, this could be a Lexus. (Why this badge? Toyota is the mothership brand, and the bosses wants Toyota to be seen as the tech leader.)

The big screen operates by touch, not by any kind of console controller. For a Japanese car, the design is clear enough and the fonts are coherent. Not something Toyota can be relied on to manage. There’s phone mirroring, too, and a useful heads-up display. Masses of actual switches mean you don’t need to dive into menus too often, though some of them lurk down by your knee where they don’t want to be found.

The shape of the cabin isn’t at all like the flat-floored airiness of a battery EV. Instead, the central tank imposes itself as a high spine down the cabin. In the front, that makes you feel tucked in, though not confined.

In the back, it’s a lot better for hire-and-reward work than the last Mirai, not least because the rear bench takes three people. Legroom is okay, but disappointing for a car this long. And in our sunroof-equipped test car, rear headroom was tight. Bit of a dropped ball, that.

Final thoughts

The Mirai needs to be regularly pounding long daily distances to make sense. Otherwise, an EV plugged in overnight does the job. Range is a claimed 653km, but that’s not a WLTP figure, so treat it with a degree of caution. Even so it looks better than EVs.

It’s not automatically a money-saving car. Hydrogen is sold in the UK by mass, and it’s at least £10/kg (P645). The Mirai’s tanks hold 5.6kg, giving fuel costs close to gasoline equivalents. That’s far more per kilometer than a pure battery car. In some other countries, hydrogen stations are closer together, and they serve locally produced hydrogen from renewable energy at a fraction of the UK price. Then the Mirai would make a case for itself.

This is a big, luxurious car. Luxury sedans with a PHEV powertrain are the same price. All-electric ones considerably more.

It’s a bit slow, but it makes up for that in refinement and comfort. The suspension is ideally set up for the sort of use the car will get. It’s a nice place to pass time and distance.

Which makes it an amazing achievement, the culmination of decades of obsessively detailed optimization and cost-reduction work for Toyota. If it can sell as many as it expects, general fuel-cell prices will fall further, from which will follow more cars and more stations.

That said, if your market doesn’t yet have the necessary infrastructure, we wouldn’t tell you to get one yet. It’s for very specialist cases—and hydrogen cheerleaders—only.

NOTE: This article first appeared on TopGear.com. Minor edits have been made.