Cultural diplomacy is a country’s soft power, as compared to hard power, wherein a country asserts its influence through military strength. Soft power is the use of the arts, language, and other aspect of culture to influence its neighbors, and in some cases, the world.

One of the best contemporary examples of cultural diplomacy is the rise of K-pop and K-dramas. Korea has exported its culture in such a way that it has permeated the countries around it and around the globe, which creates a fascination with Korean culture as a whole.

What is funny is that people do not seem to realize that before we were bingeing Squid Game on Netflix and listening to Blackpink, Japan did it first. From sushi to Initial D to Spirited Away, Japan has always been at the forefront of pushing its culture out into the world.

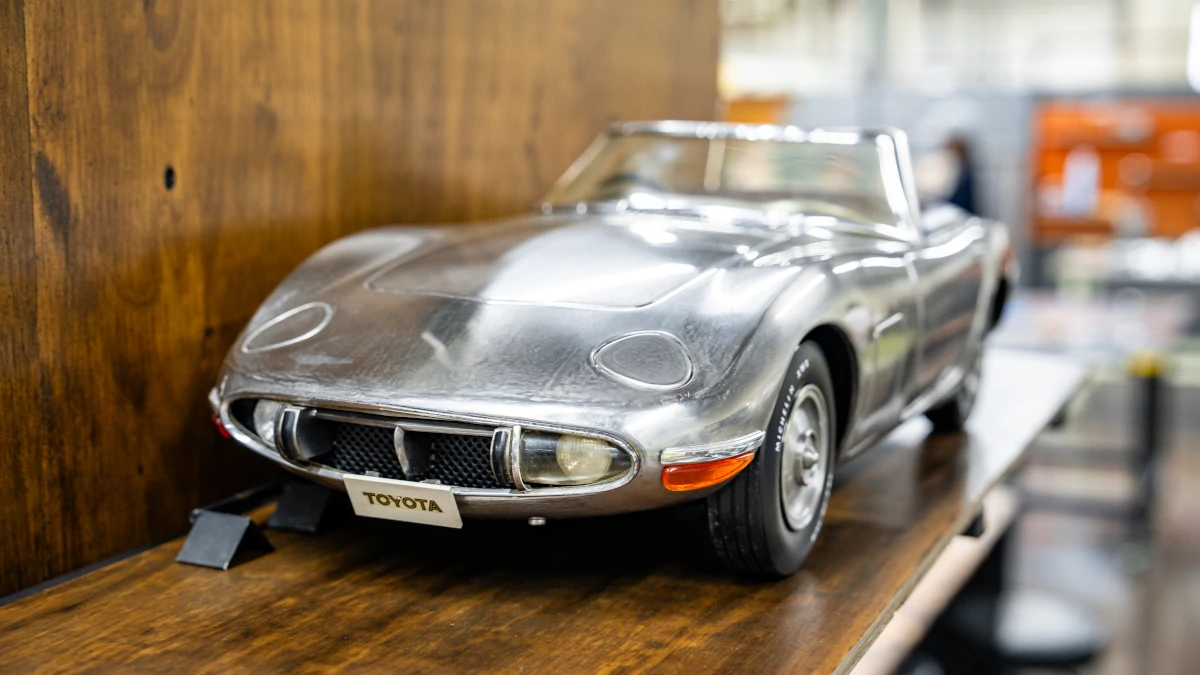

It is Japan we have to thank for why the West started to have a fascination with our region of the world. I bring this up because Lexus flew us to its home in Nagoya to visit its Shimoyama Technical Center. But before this the premium Japanese carmaker brought us to its metal crafting center and a 176-year-old sake brewery. What does this have to do with cars? The answer lies in the past.

Lexus’ first steps

When Lexus was launched as the luxury arm of Toyota in 1989, it shocked the world with its first effort–the now legendary LS400. When you read between the lines of old reviews, however, you realize that this car was built on two foundations. First is that it was a car designed to be luxurious to the tantalizingly huge American market. Second, is that the benchmarks were the large Mercedes-Benz and BMW sedans of the era.

Yes, the car was technically brilliant, and built its reputation on reliability and refinement. But reading the reviews of that time, I could not find anything that would show that there was something distinctly Japanese about the LS400.

Globalization is our new reality; the more that we are interconnected as one human race, the more homogenous we eventually become. We can especially see this in the car industry, with global platforms and equally global production, resulting in cars that feel the same, drive the same, and in some cases even look the same. Our industry has become a consequence of focus group discussions and decisions by committee. When Lexus was launched it was as guilty of this as well; understandable as it was its first foray into the luxury segment.

Reversing globalization

Something changed in the early 2010’s, however. Toyota chairman Akio Toyoda pushed a “fun to drive again” agenda with the launch of the Toyota 86 at the Tokyo Motor Show. I remember being there in person when he pulled the covers off, and I watched as tears rolled down his cheeks onstage as he talked about the challenges of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, and the troubles accompanying the largest recalls the world had ever seen.

Toyoda-san was emotional. This was his company, and he felt that the brand needed a reset. And to do this, he decreed that the cars that bore his name needed to be fun to drive above all else.

We wondered just how this passion would affect the Lexus brand, and we didn’t have to wait long for an answer. In 2013 Lexus launched the all-new IS350, and from a driving perspective we were shocked. It was so far beyond anything the brand had produced outside of the iconic LFA.

Now, the Lexus IS has always had a passionate fanbase, but anyone who has driven an older IS would know that while technically competent, it was missing that special sauce that others in its segment had. Some detractors had complained it felt too much like a Toyota, while others were claiming that it tried too hard to be European. To sum it up, the previous generation Lexus IS was in limbo as something that did not stand out in its segment; a failing, given how competitive the compact luxury sports sedans were at the time.

The all-new 2013 Lexus IS350 was the first car to genuinely feel Japanese—it wasn’t a facsimile of a European car. This was not a coincidence, said Shuichi Ozaki, the man in charge of static and dynamic performance for all Lexus models. Ozaki said that this generation IS350 was the first Lexus to see the renewed focus on handling, and the beginning of the quest to find a “Lexus Driving Signature.”

Ozaki-san is a “takumi,” a Japanese term and a real Lexus job designation for a master craftsma. Takumi specialize in just one very specific thing, and they are extremely good at their jobs.

In this case, Ozaki-san is the takumi Lexus had tasked with making the cars feel like a Lexus to drive. He told us that the 2013 IS was when Lexus finally put driving dynamics at the forefront of development. More than just having to be fun to drive, it had to define what it meant to drive a Lexus, and it had to feel Japanese.

It was from this point on that Lexus finally flipped the script, did a 180, and started forging its own path with its own signature driving feel. It was through this reverse globalization of sorts, in eschewing what others were doing, that Lexus hopes to became a tool of cultural diplomacy for Japan, embodying a car to showcase the craftsmanship of its people, imbuing a car with Japanese cultural value, and exporting it for us in the world.

Japanese culture and Lexus

This is why Lexus brought us to Hakurou, a sake brewery that has been standing since 1848, and to Lexus’ metal working shop. It wanted to highlight how it is now pivoting to emphasize how the devil is in the details when it comes to traditional Japanese craftsmanship—how Japanese heritage and culture intersects with the temperament required to excel at the smallest tasks, and how this permeates the culture of continuous improvement, or ‘kaizen’ that Lexus uses for its cars. And to this, all I can say is: It’s about time.

We are no stranger to the borderline obsessive-compulsive nature of the Japanese craftsman. Anyone who has dined at a sushi restaurant or has been fortunate enough to witness a Japanese tea ceremony knows that this is a culture of doing the very best work for even the most menial of tasks. The pursuit of perfection, if you will.

Applying this to Lexus cars, you can only imagine how a takumi whose task is solely focused on vehicle dynamics would focus obsessively on the smallest of details. It is the reason why Lexus opened the Shimoyama Technical Center, a state-of-the-art facility in the mountains of Nagoya that focuses on only one thing: The continuous improvement to make ever better cars.

The Shimoyama Technical Center

Shimoyama is basically the holy grail of Lexus development. A technical center built on 6.5 million square meters of land, it serves as the home of Team Lexus—one team under one roof. Incorporating a garage, office, and design center, it is a one-stop shop for applying ajimigaki, or ‘flavor and polish’ to Lexus cars. The reason they can do this is that Shimoyama was built with the most sophisticated test track we have ever driven on.

The track, which is inventively named Test Course No. 3, embodies the philosophy of “roads build the car.” It was patterned after the Nürburgring but with a twist: Lexus purposely made the track worse. It has blind corners, jump spots, off-camber corners, very uneven high-speed elevation changes, and perennial Filipino favorites, potholes and uneven roads.

This was in no way meant to be a race track. Test Course No. 3 was designed as a torture test of sorts. This proving ground is meant to swallow up lesser vehicles and highlight the very worst of their designs through the application of consistent, but fair, road conditions in a controlled environment. It is so tricky in fact, that a Toyota GR Yaris crashed by Akio Toyoda is showcased in the lobby; proof that even the great Morizo is not immune to the call of the barrier around here.

Shimoyama is absolutely brilliant. Test drivers can pilot the vehicle through a few laps and make notes on how the vehicle behaved compared to how it should have behaved in their minds. And because the garage and the engineers are stationed on site, they get instant feedback to make immediate tweaks to the car and find solutions to problems made apparent by the track. This is the spirit of “genba” or “where the work happens.”

By having a facility like this, where the drivers can work together in a collaborative environment with the technicians and engineers. The former are empowered and better able to express their impressions, and the latter can easily make on-the-spot adjustments before sending the drivers out for another few laps and another few tweaks to the formula. Rinse and repeat, and you have what is the most direct application of continuous improvement we have seen in a brand.

Moving forward

We were told that for most other car companies, the launch of a new vehicle is the end goal, while for Lexus, it is just the beginning. From the moment a vehicle is launched, Lexus immediately starts the cycle of testing and improvement, of ajimigaki.

So while a Lexus may look exactly the same on paper every year, tweaks may have already been applied to the chassis, suspension, even the engine—adjustments care of Shimoyama.

It takes a special kind of company to admit that something that it has just launched can be improved, and that the act of releasing a car is just the beginning. But this is Lexus, and for them, this is its obsession made manifest.

More photos from our Nagoya experience: