This week, the last ever Bentley Mulsanne rolled down the production line. Within it lies the very last 6.75-liter V8. And, somewhat oddly, it’s the engine rather than the car that we’ll mourn most. The Mulsanne is 10 years old. It replaced the Arnage, which came after the Turbo R, which dovetailed with the first Mulsanne, which supplanted the T-Series cars, which superseded the S-Series. That’s a lot of history—over 60 years of grand Bentley sedans, in fact, and the same V8 engine has thrummed, roared, rumbled, and sung under the hood of each and every one of them.

Here are the 11 things you need to know about the death of the engine...and the car that now dies with it.

1) It now develops over 200% more power.

The L-Series engine (technically L410, after the 4.1-inch bore size) first appeared in the 1959 S2, and back then, it wasn’t a 6.75-liter at all, but a 6.25-liter. The capacity of experimental versions went as high as 7.5 liters, before settling at 6.75 liters in 1971 (the stroke was lengthened from 3.6 to 3.9 inches). It’s been developed, of course, but when Bentley says it’s the same engine, the aluminum block still has the same bore measurements and cylinder spacing, and the heads retain two valves per cylinder driven by pushrods on a single camshaft.

Originally, the L410 developed around 180hp. In its latest guise, under the broader but shorter hood of the Mulsanne, it develops 530hp and a massive 1,048Nm. Almost three times the power, but here’s the stat I really love. So much cleaner is the engine now (emissions are down 99%) that the new engine could idle on the tailpipe emissions of the old one.

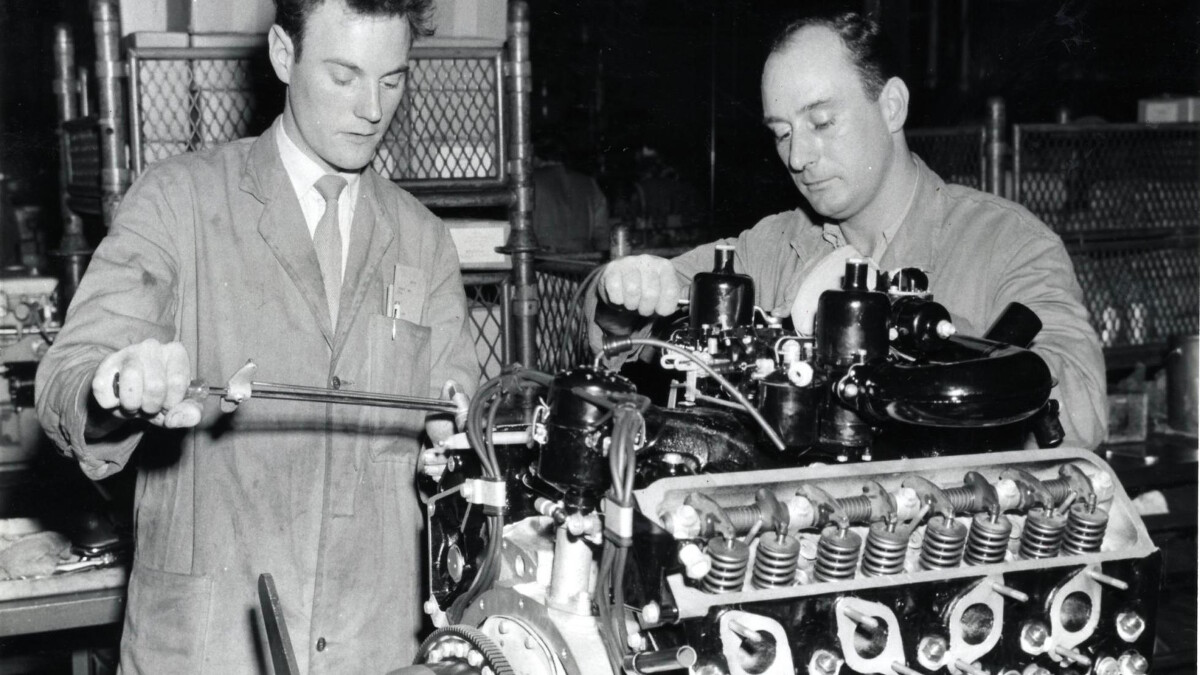

2) It replaced a straight-six.

Here’s one being assembled sometime in the ’60s—you can see the pushrod-actuated valves and the beefy springs that supported them. The engine had a tough brief when it was first developed. It was replacing a straight-six that dated back to 1922 (two engines spanning almost a century of car development), and the new V8 was tasked with boosting power and torque by 50%, matching it for noise, smoothness, and reliability, and being no heavier or larger—it had to fit in the same space without styling or structural alterations.

It managed all of that (casting the block from aluminum rather than iron certainly helped, as it was 14kg lighter), and I think we can confidently say that it exceeded the final part of the brief, which was that “bearing surfaces should be large enough to allow a 15-20% increase in power and torque over the lifetime of the engine.” Nailed it.

3) No other car produces more torque this low down.

There’s much to be said for engines that don’t rev. Of course, we all love revs in sports cars, but frantic, fizzing engines just aren’t right for luxury cars. In those, you want effortless torque as low as possible—and none delivers more of it, or lower down than the 6.7-liter. In its latest, mightiest iteration, the twin-turbo V8 delivers 1,098Nm at 1,750rpm. Or 811lb-ft (and six-and-three-quarters) in the imperial system. Everything about this car is definitely imperial.

And yes, the engine really does only rev to 4,500rpm (plus the needles sweep smoothly south). Why do you need more, though? The Mulsanne is long-geared, but has so much shove from 1,750rpm that you rarely find yourself going beyond 3,000rpm. These days, almost every diesel revs higher. Which brings me on to another point. Now, I might have this wrong, because this goes back over 15 years, but I’m sure I remember Bentley’s then engineering director, Ulrich Eichorn, telling me the 6.75-liter was so strong that they tested it without a spark plug, whacked up the compression, and ran it on diesel—and the block took it.

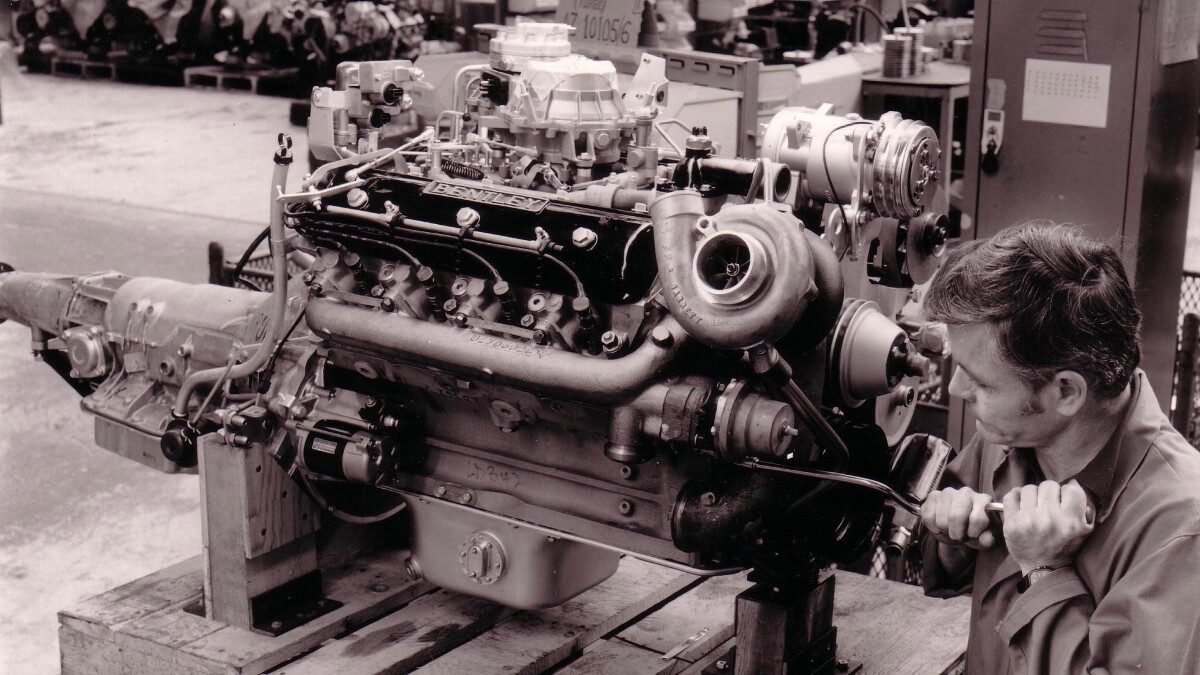

4) It was an early adopter of turbocharging.

In 1982, Bentley turbocharged the 6.7-liter. It was the first ‘blower’ Bentley since the Birkin era and pushed up power and torque by 50%. The carmaker didn’t talk about such uncouth specifics as power and torque back then, instead suggesting it developed something in the order of 300hp and 609Nm—enough to yield 0-60mph (97kph) in 7sec.

The engineers had looked at fitting a Garrett turbo per bank, but there wasn’t enough room in the engine bay. The original Mulsanne Turbo carried no suspension or bodywork changes, just a small badge and a bigger price tag—up by over £6,500 to £59,000. But it was an instant success, and it’s no stretch to say this is the car that saved the company.

5) It’s not exactly responsive.

Remember what I said about revs? You don’t need ’em. Same goes for response. You just need to plan better. The engine has a huge amount of inertia in it—you’re overcoming not just turbo lag, but also piston weight, flywheel effect, crankshaft—so building up a head of steam takes a second or two. But then it does the full runaway locomotive, and it’s chuffing fast.

Speed builds quickly, and when you lift off, it doesn’t diminish at all—the Mulsanne has unstoppable rolling momentum. So, you find yourself feeding the engine gobs of torque via the long-travel throttle. There’s a distant churn of noise, the nose picks up and, after a short, while you lift off; the noise dies away and you sweep serenely on.

It’s not the smoothest or most refined these days (a Merc V12 is superior in both regards), but a Bentley shouldn’t be silent—it should have charisma. The engine doesn’t have a particularly memorable noise signature. There’s no quaking V8 roar; instead it has presence. You’re always aware of a distant rumble and hum, giving it more in common with a cross-channel ferry than you might expect.

6) What’s wrong with body roll, anyway?

The engine defines the car. So, it rolls like a nautical vessel as well. There’s nothing wrong with that. Roll lets you know a car is working. Sure, there’s something semi-delinquent about going fast in a Mulsanne, even one with a Speed suffix, and initially, it feels quite ponderous. Throttle and brake pedals have to be pushed a long way, and the steering (with an unfashionable 3.5 turns between locks) needs a good long sweep. It comes across as lazy and reluctant.

So, I went and drove it for a hundred miles, and I completely changed my mind about it. It’s not lazy, it’s just deliberate. It gives you time to correct your mistakes, and convinces you not to rush about, but instead to follow the car’s lead. Not slow down, but realize that there’s a certain pace at which the Mulsanne is perfect, a certain way it likes to be driven. You slow down earlier, calmly select the correct gear (you rarely need to call on one lower than fourth), and gently introduce some power back in before you arrive at the apex. The car adopts its chosen roll angle, settles, then surges onwards. It’s far more composed than you expect.

7) It generates enough heat to warm a stately home.

Lift the hood after any drive (and you will because you’ll want to admire the work done by—in this case—Ian Allcock), and you will inadvertently take a step back as you realize that what you’ve just opened appears to be a giant oven door. It gets hot under there, even after short, modest trots and even though the engine only pulls 1,550rpm at just past 110kph in top.

Much heat is the result of much fuel being burned. Yes, you should get over 640km per tank, but that tank is almost 100 liters. At a stately cruise, you’ll get 9.8-10.2km/L, which is good, seeing as that falls to sub-6km/L if you get carried away.

8) Nothing else looks or feels like this.

Except maybe an aircraft—there are a lot of dials, buttons, and switches about the place. You sit high, at crossover altitude, and survey the outside over that proud hood. Yes, you look like it’s the late ’80s and you’re chauffeuring a billionaire around, but you won’t care a jot because it feels good.

9) It feels nothing like a Volkswagen.

The Mulsanne doesn’t predate Volkswagen’s ownership of Bentley. The Crewe marque had been under German ownership for 12 years when the Mulsanne appeared, but for some reason, this proud machine with its signature motor seems to have been immune to the effects of Wolfsburg. While the Conti GT, the Bentayga, and the Flying Spur all have matched platforms, engines, and components with other cars across the group, the Mulsanne stands alone.

That’s not to say the Mulsanne is a bespoke one-off—it’s not, but the shared componentry is better hidden and disguised here. Often, it must be said, by being quirkily flawed. I searched high and low for a recognizable VW part. This was literally all I could find—the handle for the compartment under the trunk carpet.

10) It has a drawer for your phone.

Maybe not so much quirkily flawed as idiosyncratic, but here’s an example of what sets the Mulsanne apart. It has a USB slot. Just the one, and it’s tucked away in a drawer. Which means that’s where your phone has to go, because if you shut the drawer with the lead poking out, the drawer gets stuck. Phone too big to fit? Most of them are—deal with it.

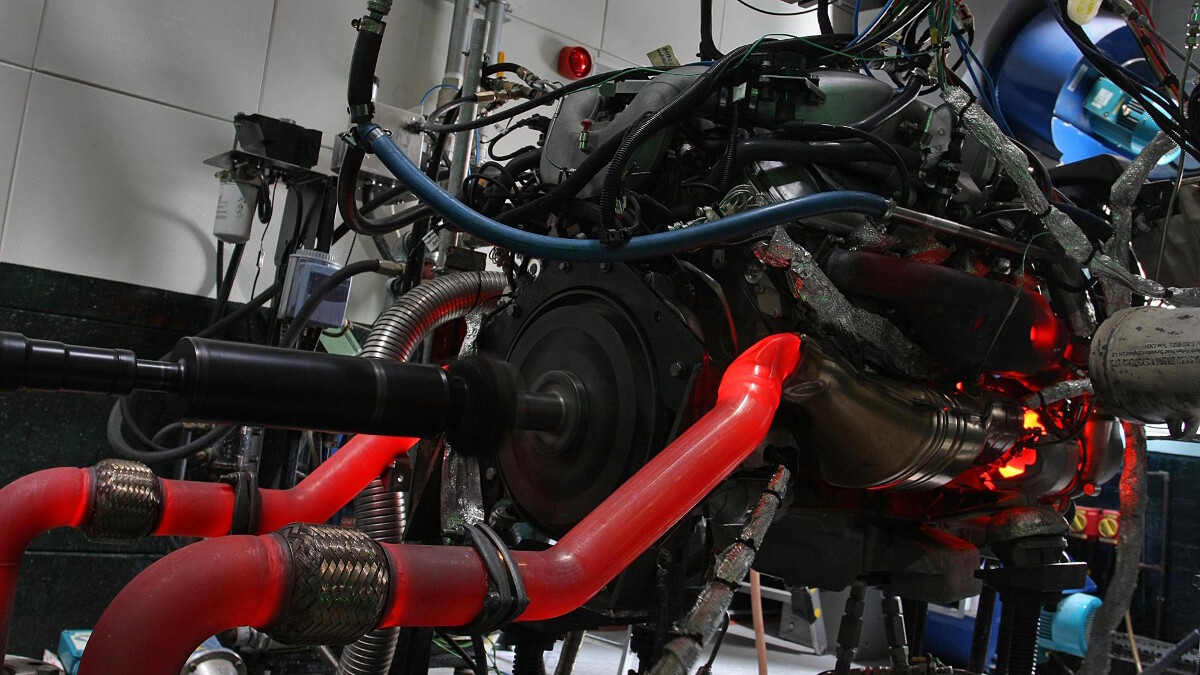

11) It was tested for many, many, many hours.

Here’s the modern engine working so hard, its exhaust and turbos are glowing red. Maybe it’s running a Le Mans program. Because it could. The 6.7-liter’s sign-off process includes 100 hours of running at full throttle, 100 ‘scuff’ tests (applying full throttle within 30sec of a -10 degrees Celsius engine start, and the ‘Deep Thermal Shock’ test. Here the motor is run at full throttle until it reaches 110 degrees, then it’s turned off, flushed with coolant at -30 degrees, then restarted and run back up to 110 degrees. Then they do the same again. And again. In fact, they do it 400 times.

But this is nothing new. The original 1959 engine was only signed off after it spent 500 hours at full throttle. That’s three weeks.

In total 36,000 of the 6.7-liter motors have been built over the last 61 years, 7,300 of them finding homes in the current Mulsanne. It is the longest-lived production engine in the world (GM and Ford have V8s that date back further, but they’re now only available by themselves, not fitted in current cars). We will not see its like again—and in the era of electric motors, nor will we care.

NOTE: This article first appeared on TopGear.com. Minor edits have been made.